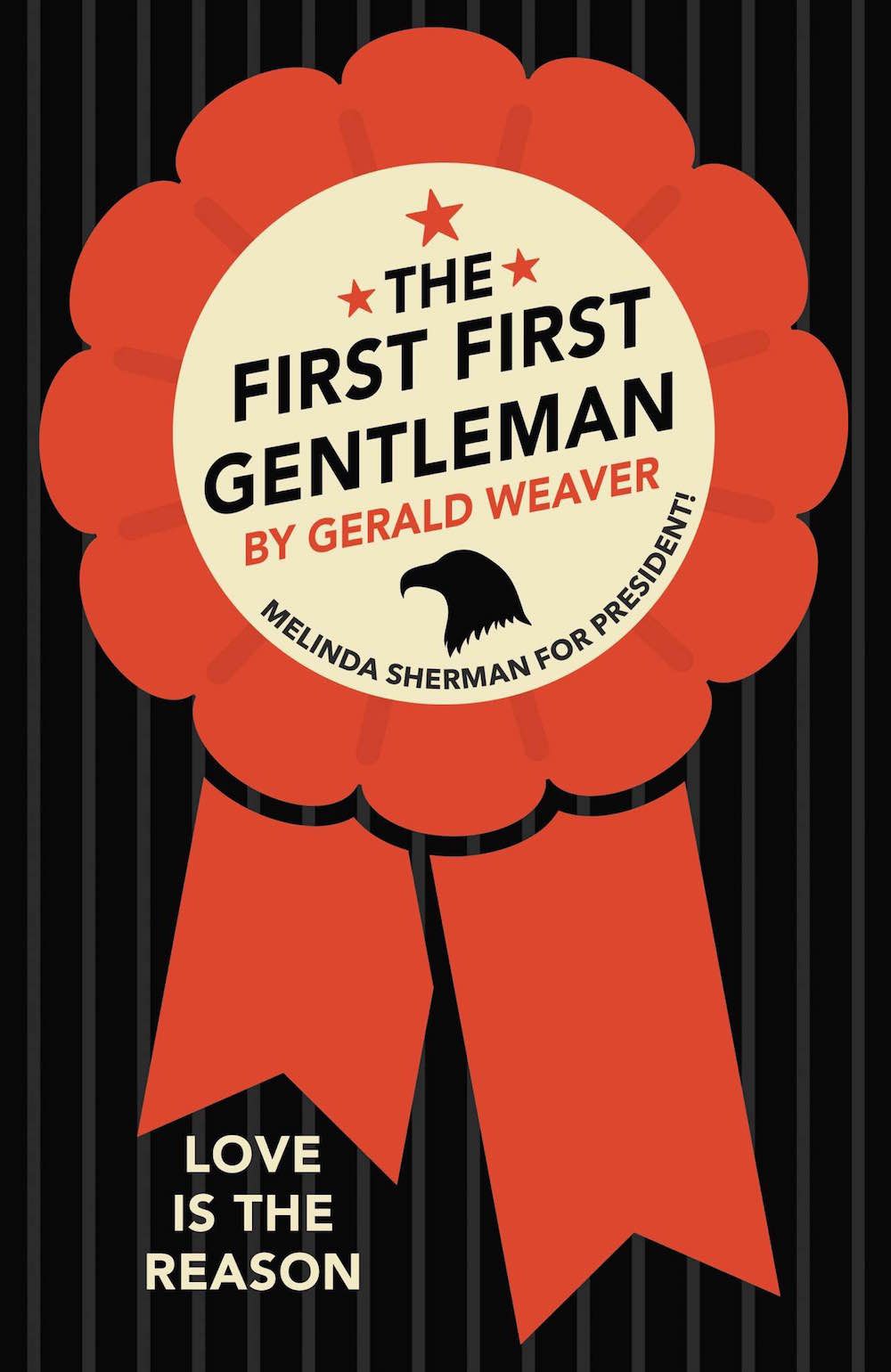

Gerald Weaver's unconventional life reads like a novel, which could be why the Yale-graduate-turned-promising-young-lobbyist-turned-teacher-turned-stay-at-home-dad–among a few other detours–has most recently reemerged as an author. In his new venture, Weaver creates narratives that often seem to touch on his own experiences and his unusual journey through politics. His latest novel, The First First Gentleman, follows the rise of Melinda Sherman, a politician who works her way to the Oval Office, assuming the role of the first female President of the United States. Weaver’s tale reflects the current state of politics, quite by coincidence. Justluxe spoke with Weaver about his past, present, and future.

You’ve had a very interesting career trajectory.

My career path has been interesting. With the sole exception of a year and a half in prison, I’ve been fortunate to always land on a new track never far from my social and economic origins. Most who go through the prison system are not so fortunate.

I began at Yale, went to law school, worked on Capitol Hill, then as a lobbyist at a law firm, and then I had my own lobbying firm… before those wheels came off. After I was released from prison, I was the stay-at-home dad. My then-wife, who I met at Yale, was the family breadwinner. At that time, I was also able to do some legal work, including manage the lawsuit against my criminal lawyer for his conflict of interest, which netted a significant settlement.

Later, a local school board hired me as a teacher after their investigator decided that the case against me had been politically motivated and that I posed no threat to the schools. The divorce court made a similar decision when I awarded child support and custody of my two children. I then remarried a woman, who had also gone to Yale, and she gave me a pathway into collecting Chinese antiquities, which then provided me with enough income that I could take the time to write.

I am not so much skilled, as I am fortunate. But I have had an interesting life… perhaps too interesting.

You were the youngest Chief of Staff in Congress at the young age of 26, but ended up serving time in prison for obstruction of justice, conspiracy to distribute cocaine and distribution of cocaine. What were your main takeaways from those experiences?

I don’t want to say that everyone should go to prison, but it is a uniquely edifying experience. There are many lessons to be learned. When I was inside, I never missed the glamour or the power of my previous position. I never missed the junkets or my expense accounts. I only missed my children and my wife. I probably cried at least once a day. Prison was a wakeup call about all that is important. It helped me to set my priorities straight and it made me a much better father.

Some of the men I knew inside said going to prison is like dying and coming back to life, all while being able to observe and to feel the effects of your own death or absence. And you get to see how things can move forward without you. That is a useful way to see things. I love Dickens, and it is a bit like A Christmas Carol.

I had been a recreational user of marijuana and cocaine, but had ceased using over two years before my prosecution. I was charged as a member of a conspiracy comprised of several friends whose continued use was applied to my case. Members of conspiracies are liable for all the actions of the conspiracy, even after one has left it. All these friends were granted immunity. I certainly learned the value of not breaking the law, ever… but the larger lesson I learned is that the War on Drugs in America has placed far too much power in the hands of prosecutors, and it’s overarching effect is that it is the most institutionally racist program since slavery. I was able to read the cases of many innocent black men while in prison.

Your first novel, Gospel Prism, was published after the manuscript was uncovered in the knapsack of slain journalist Marie Colvin, the acclaimed war correspondent who wrote regularly for the UK’s The Sunday Times. How did that experience affect you?

Marie Colvin and I had dated in college and, afterward, remained friends for almost forty years. She inspired me to write Gospel Prism, and she served as my writing coach and she also made broad editing suggestions. She had even spoken to literary agents about my novel, because she knew several who were interested in her life story. She was a brilliant and beautiful woman. John Witherow, her senior editor at The Sunday Times called her the greatest war correspondent of her generation. She had won multiple journalism awards. She was also exceedingly generous, and utterly brave. She covered stories from which others shrank.

When I learned of her death, I was in shock, not only because of the personal loss, but because we all have a feeling that certain people are too vibrant and too vital and too larger than life for us to ever imagine them dying. When I learned that she had died with my manuscript on her, I was not surprised. It was just like her to do such a thing, to task herself with reading and editing my novel while she was under fire. That tremendously honored me, but I also saw it as a terrifying duty, to refine the novel, to get it published, and to promote it.

How would you describe Gospel Prism?

Christian, the skeptical hero of Gospel Prism, receives a midnight visitation from the beautiful mixed-race Messiah, who tasks him to solve a series of spiritual mysteries in order to save his immortal soul. His investigation takes him on a spiritual quest, leading him to a surprisingly fresh new look at how we all must read the written word, and change our understanding of its relationship to religious faith.

The twelve stages of this adventurous journey bring Christian into unpredictable contact with a mafia don, a famous journalist, a heroic hit man, his own wife, a worldly and wise rabbi, a vengeful prison guard, an impish pyromaniac, the memory of his own mother, and the actual residents of Hell, among others. He also learns that the story of his odyssey is already being read by many and perhaps worshiped by the few, for whom it becomes a type of secular bible.

His fateful final appointment with his nocturnal visitor looms at the end of the dozen chapters of his journey, each of which yields a revelation that informs and entertains the common reader but which the more erudite reader will recognize as the paraphrasing of great works of literature by Cervantes, Shakespeare, Tolstoy, Whitman and others.

Christian perhaps discovers where wisdom may be found, what may be the best way out of each person's figurative prison, and that perhaps the world's last great religion is reading. It is an ambitious novel, but readers have enjoyed it.

Your new novel is The First First Gentleman. Is the narrative informed by the current political climate? Did Secretary Clinton's run for first female President have influence or is the timing merely coincidental?

I actually wrote The First First Gentleman mostly in 2013. The original US copyright on the first manuscript is April 2014, so the novel is an accurate predictor of much of what is happening – not so much that we will have a woman Presidential nominee for a major party, that could have been foreseen, but at the core, the novel is about how this female candidate violates the political orthodoxies to find a strong following because she is unafraid to say what she really thinks.

In fact, my purpose was not to tell a story that corresponded with Secretary Clinton, but to tell one that actually and accurately anticipated the appeal of Bernie Sanders. I have long believed that voters are tired of cautious politicians and that someone who could come and take a bold or unpopular position would be seen as a leader. I have also long felt that there are certain cultural orthodoxies, such as the War on Terror or the War on Drugs, that are never debated, but should be, and that the person who will start debating these issues will enter a leadership role.

My female candidate is iconoclastic, not at all like Hillary. Still, she shares what I think is overlooked in this country, and that is the fact that having a woman President will be an exciting watershed moment, even more so than having an African-American President, who in a sense is just another guy who went to Columbia and Harvard.

What kind of research did First First Gentleman entail? Did yo