Rediscovering New England Part 2: The Berkshires Beyond the Postcard

I grew up in America’s Northeast but, like many, I left in search of what I thought were more exciting landscapes. Life carried me to Europe, Australia, Vietnam, even Iceland. Decades later, returning to rediscover the region, I didn’t expect much. As we know, the grass is always greener on the other side—or so it seems. What I found instead was a place transformed: not simply familiar scenes from memory, but something layered and surprisingly alive.

This is the second part of my journey through America’s New England. The first followed the Massachusetts coast, where fishing towns and sea air shape daily life. Later will come New Hampshire, Connecticut, Rhode Island, and finally, the defacto capital of New England, Boston. Here, in this article, we turn to the Berkshires—New England’s escape to the mountains. The place Londoners would compare to the Lake District or New Yorkers to the Poconos. A refuge of clean air, rolling hills, and perhaps the world’s most spectacular autumn, when green dissolves into golds and reds before surrendering to brown.

For me, the beauty of fall was once just a most dreadful chore. My childhood autumns were spent with a rake in hand, corralling endless drifts of leaves into waist-high piles—weekend after weekend, until the first frost finally ended the ritual. What I once dismissed as tedious now reads differently: the vivid blaze of maples shifting from green to gold, the rustle of dry oak leaves underfoot, the smell of woodsmoke curling from chimneys. Returning after decades abroad, the Berkshires allowed me to see New England with fresh eyes —a piece of America that is both familiar and entirely new.

A Journey through the Berkshires

The Berkshires are western Massachusetts distilled into its most elegant form: a sweep of mountains and valleys where nature, culture, and history converge. The landscape is both gentle and dramatic—rolling fields framed by stone walls, dense forests that erupt into fiery color each autumn, and villages whose church steeples still rise above shaded greens. Long the summer playground of writers, artists, and New York’s moneyed set, the region balances rustic quiet with intellectual energy; Gilded Age mansions and literary estates sit alongside contemporary galleries, experimental theaters, and symphony halls. Once sustained by mills and industry, its towns are now defined by reinvention, drawing chefs, artisans, and entrepreneurs who see possibility in its historic bones. To speak of the Berkshires is to speak of an American ideal—pastoral yet sophisticated, rooted in tradition yet endlessly renewed by imagination.

The approach itself sets the tone. From the Massachusetts coast, the three-hour drive west passes farmland and small towns until the roads narrow and curve into the hills. A farm stand here, a red barn there, and then a wooden covered bridge—timbers creaking softly under the tires, sunlight striping through narrow slats—mark the quiet passage into another world.

Stockbridge and the Red Lion Inn

The town of Stockbridge feels almost painted into being and it should be, that is where Norman Rockwell took inspiration for a number of his most iconic pieces. There you’ll find white-steepled churches rise above the trees; brick storefronts house farm stands with baskets of apples and late-summer corn; antique galleries display glassware and porcelain plates and brass chandeliers from a century ago. Couples of every age appear on the sidewalks. A young family pushes a pram while across the street, an elderly pair walks their golden retriever, which seems to pause at every lamppost. The seasons of life are visible here just as the maples above shift from green to crimson to bare.

At the center of town is the Red Lion Inn, a white clapboard hotel that has stood since 1773. Its wide porch stretches across the front, lined with wicker chairs and hanging ferns. Breakfast here is tradition and as it has been for the last 100 years, pancakes stacked high, maple syrup poured without fuss, coffee served in thick white cups that retain their heat.

Inside, creaking staircases lead to guest rooms furnished with four-poster beds and braided rugs. Walking the halls, it is easy to imagine the generations of travelers who have stayed here: soldiers returning from war, city families seeking air in the hills, and today’s visitors drawn by both nostalgia and comfort. The Red Lion is not retrofitted Americana—it is the real thing, continuity embodied in wood, fabric, and ritual.

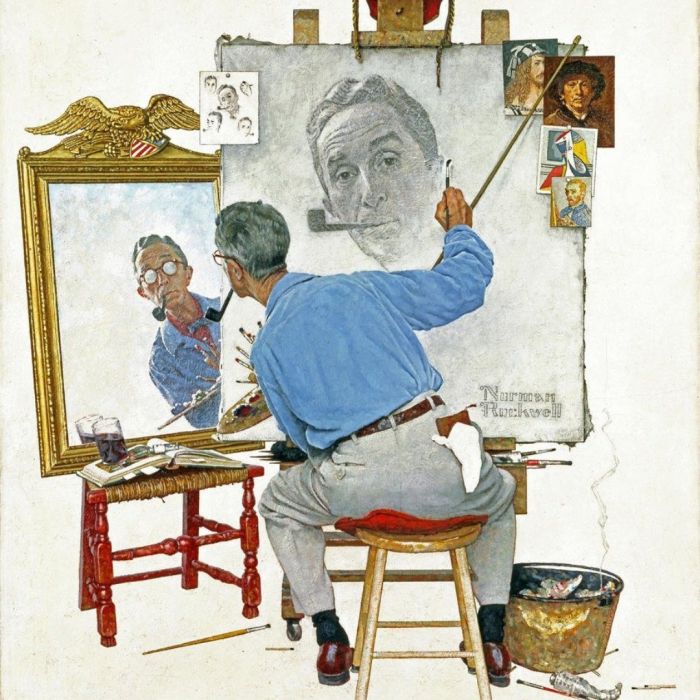

The Norman Rockwell Museum

Few artists have captured the American imagination as vividly as Norman Rockwell, and his museum, just outside Stockbridge, is both archive and mirror. Inside, walls carry the familiar images that once arrived weekly on the covers of The Saturday Evening Post: a boy perched nervously in a barber’s chair, a family gathered for Thanksgiving dinner, small-town policemen guiding children across the street.

The Saturday Evening Post was a staple of mid-century American life, a weekly mix of stories, news, and illustration, and Rockwell’s covers became its defining face. Later, Look—a more modern photo-driven magazine that confronted social issues and cultural change—gave him the freedom to take on weightier themes, from poverty to civil rights. He was prolific, creating thousands of illustrations across these and other outlets, including playful contributions to Boy’s Life and even Mad Magazine, where his presence carried a sly irony in a publication devoted to lampooning American institutions.

Humor ran through his work too. Rockwell often slipped himself into his paintings, sometimes in plain sight, sometimes as a subtle figure in a crowd—self-portraits hidden in plain view, part joke, part signature. One of his most striking canvases, The Problem We All Live With, shows Ruby Bridges, a six-year-old Black girl, walking to school under federal protection—an image that distilled both innocence and defiance into a single moment.

To move through the galleries is to experience America in fragments: idealized, satirized, questioned, celebrated. A docent explains how Rockwell labored over facial expressions, adjusting the tilt of an eyebrow until it conveyed precisely the right shade of emotion. And there, just up a hill, sits his restored studio: a modest room with a drafting table, brushes arranged in jars, and windows framing the Berkshire hills in soft light. Standing there, one can almost hear the scratch of pencil on paper, the pause as he looked outward before turning back to his canvas. His genius was not in grandeur but in noticing the little things such as the curve of a smile, the tension of a glance, and then transforming the everyday into the enduring.

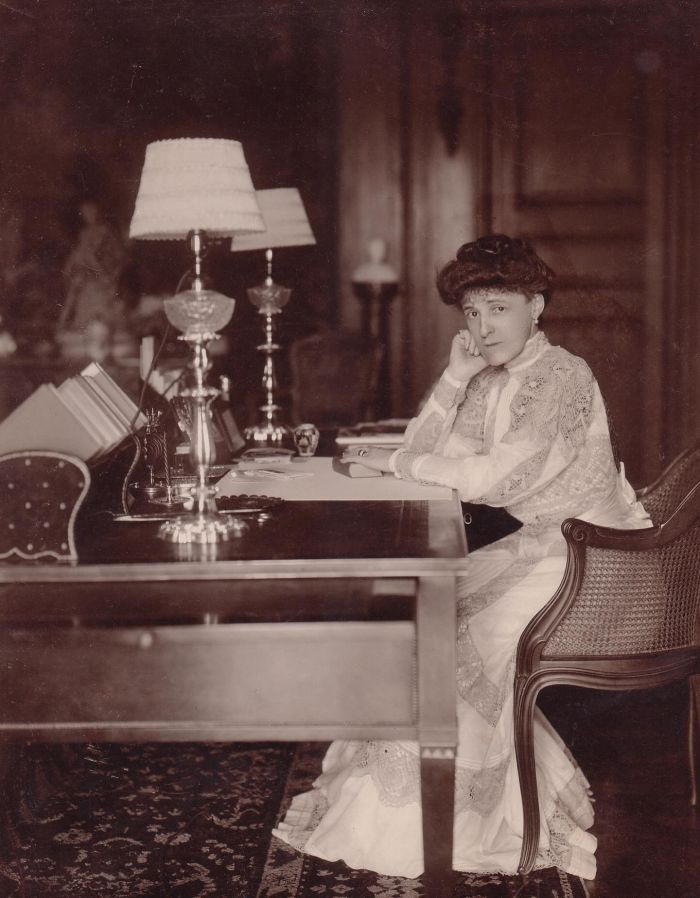

Edith Wharton &The Mount Estate

While Rockwell gave Americans their pictures, Edith Wharton gave them their stories. Her estate, The Mount, just outside Lenox, rises on a hillside with sweeping views of Laurel Lake and the Berkshire hills. Completed in 1902 on a 113-acre parcel, it was her “first real home,” where classical proportion, refined simplicity, and thoughtful functionality combined with personal comfort. The house evokes the elegance of European estates, recalling the symmetry of an English country manor and the stately presence of an Italian villa, while the gardens and terraces frame the landscape with deliberate grace, reflecting Wharton’s eye for both design and narrative.

Born into New York high society, Wharton became one of America’s most formidable novelists. She examined the rituals, manners, and unspoken codes of the elite with extraordinary precision in works such as The Age of Innocence and The House of Mirth. In 1921, she became the first woman to win the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, a remarkable achievement in an era when women of her class were largely expected to host salons rather than shape the literary landscape. Her family’s prominence endures through the Wharton School of Business, yet The Mount embodies her personal vision, creativity, and artistic independence.

Wharton designed the house herself applying classical principles while adapting to the rugged Berkshire terrain. Visitors can explore French-style gardens where hedges form intimate green “rooms,” wander woodland paths punctuated with contemporary sculptures, or simply take in the views from terraces designed to frame the hills and distant lakes. At midday, the Terrace Café offers a quiet pause. Tables overlook the expansive lawns and curated gardens, inviting reflection on a woman who built a literary life on her own terms.

Bold Brewing in Pittsfield at the Hot Plate Brewery

Not all of the Berkshires is postcard-perfect. Some towns still carry the bones of their industrial past, with brick mills, shuttered factories, and streets more utilitarian than quaint. Yet here too, renewal is taking place. Creative entrepreneurs are transforming abandoned spaces into galleries, workshops, and breweries. One of the most notable is Hot Plate Brewing Company, founded by Sarah Real, a Latina brewer with a vision to put Pittsfield on the craft beer map. Her taproom hums with conversation, locals stopping in after work, weekend travelers sampling flights, laughter spilling across reclaimed wood tables.

Inside the former Pittsfield storefront, vacant since 2016, an exposed-brick, reclaimed-wood taproom hums with energy. The space was designed to feel like a welcoming friend’s apartment, with a lounge for conversation, a board game area, and a wheelchair-accessible bar. Beyond sliding glass panes, the brewhouse is on full display. Gleaming steel tanks and copper piping catch the soft light, while the rich aromas of mash and hops fill the air. The taproom walls display awards and mission-driven statements, including their motto, “Do what you can with what you have,” a guiding philosophy that speaks to both grassroots beginnings and intentional community building.

Beer has long been part of the region’s fabric, from colonial taverns and industrial-era breweries that kept mill workers fueled to internationally recognized names such as Samuel Adams, which now sit alongside a flourishing craft scene. Sarah Real leads head brewing operations with precision and creativity, honoring that lineage while reinventing it. Local grains, hops, and occasional foraged ingredients find their way into every batch, from citrus-forward IPAs to velvety stouts with hints of chocolate and coffee. Signature offerings include chamomile blonde ale, jalapeño pale, and Capable of Anything, a chamomile-infused blond ale now distributed widely, each brewed with technical skill and a fearless sense of experimentation.

The name honors her and her husband and partner’s Brooklyn beginnings. After the gas was cut off in their apartment, Sarah began brewing on a simple electric hot plate, which now hangs above the bar as a symbol of persistence and purpose. Today, Hot Plate is more than a brewery; it is a gathering place, a testament to resilience, and a symbol of a town carving out its next chapter.

It is not just about tasting beer here. The originality of the brewery’s founding, the visible process in the glass-walled brewhouse, the warmth of community, and the clear purpose behind each brew make Hot Plate Brewing less a stop on the road trip and more a gathering point, a creative hearth in the heart of the Berkshires.

Sarah, whose brewing journey began humbly in her kitchen and later on a simple hot plate, is now a board member of both the Massachusetts Brewers Guild and the Pink Boots Society.

A century ago, Edith Wharton carved out a place for herself in a world that offered women few avenues to do so. Her vision, independence, and determination reshaped the literary and cultural landscape of her time. Today, that same spirit finds a new expression in women like Sarah Real, whose creativity and ambition are redefining what it means to lead and innovate in the Berkshires.

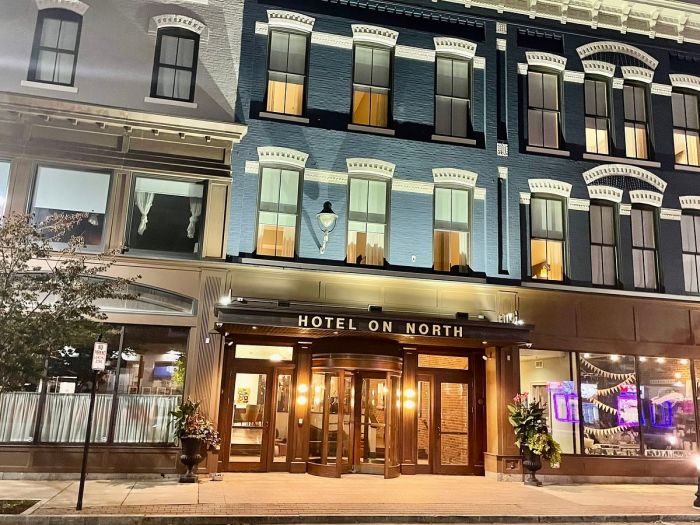

Pittsfield and a stay at the Hotel on North

Staying in the Berkshires often means choosing between historic inns and rural retreats, but Hotel on North offers something distinct: a blend of heritage and modernity within the heart of Pittsfield. Housed in two restored 19th-century buildings, the hotel’s most striking feature is its central atrium. Rising several stories high, the space is framed by original exposed brick and iron beams, light cascading from above. It feels both industrial and elegant, a reminder that the Berkshires’ past is not erased but reimagined.

Guest rooms balance history with comfort. Antique furniture mixes with contemporary design, and no two rooms are identical. The Library Suite stands out: shelves stacked with hardbound volumes, leather chairs softened by use, a fireplace anchoring the room in quiet warmth. It feels less like a hotel and more like the home of a well-read friend who has momentarily stepped out.

Reflecting on the Berkshires

The Berkshires are not a single story but a collage: towns reinventing themselves after industry fades, cultural landmarks rooted in history, landscapes that remind us of both continuity and change. They are Norman Rockwell’s Americana and Edith Wharton’s society dramas; they are porches with pancakes at the Red Lion Inn and craft beer brewed with vision in a converted mill.

For those seeking a retreat, this is not an escape into fantasy but into texture and change—the shift of the seasons, the weight of history in brick and timber, and the quiet energy of communities reinventing themselves

Returning here after years away, I realized the grass is not greener elsewhere. It is green here all along, in the rolling hills, in the fields edged with stone walls, in the renewal of a place that is quintessentially American.